Climate Change as a Threat Multiplier: Human Security Risks in Gilgit-Baltistan

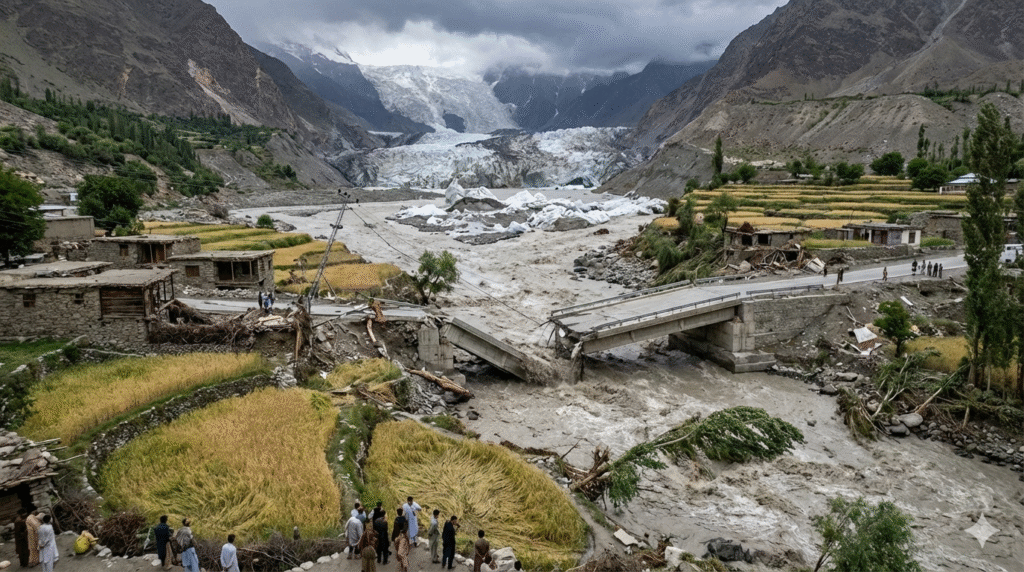

The Threat Multiplier: From melting glaciers to devastated infrastructure, climate change creates a cascading crisis for human security in Gilgit-Baltistan.

Climate change is increasingly understood not as a standalone environmental problem but as a threat multiplier that amplifies existing social, economic, and political vulnerabilities. Nowhere is this dynamic more visible in Pakistan than in Gilgit-Baltistan, a mountainous region where climatic stress intersects with fragile livelihoods, difficult terrain, and limited institutional capacity. In this context, climate change is reshaping the human security landscape by intensifying risks to lives, livelihoods, mobility, and governance, turning environmental disruption into a strategic challenge with long-term implications.

Gilgit-Baltistan lies at the intersection of the Hindu Kush, Karakoram, and Himalayan ranges and hosts one of the world’s largest concentrations of glaciers outside the polar regions. These glaciers have historically served as natural water reservoirs, regulating seasonal flows and supporting agriculture, hydropower, and ecosystems both locally and downstream. Rising temperatures, however, are altering this equilibrium. Accelerated glacier melt, erratic snowfall, and shifting monsoon patterns are undermining the predictability of water availability while increasing the frequency of extreme events such as flash floods and landslides. The result is a dual risk: short-term disasters and long-term water insecurity.

From a human security perspective, the most immediate threat is to physical safety. Glacial lake outburst floods and sudden flash floods have become more frequent, destroying homes, schools, roads, and health facilities. In remote valleys, limited early-warning coverage and difficult access mean that communities often receive little notice before disaster strikes. These hazards disproportionately affect already vulnerable populations, including subsistence farmers and pastoralists, for whom the loss of a single harvest or grazing season can have lasting consequences.

Livelihood insecurity is a second critical dimension of climate-related risk. Agriculture in Gilgit-Baltistan depends on meltwater-fed irrigation systems that are finely tuned to seasonal cycles. As glaciers retreat and hydrological regimes change, farmers face uncertainty in planting schedules and declining yields. Pastoral communities experience shrinking and degraded pastures as temperature changes alter vegetation patterns. These stresses erode income security and push households toward coping strategies such as seasonal migration, debt accumulation, or reliance on external assistance, all of which reduce long-term resilience.

Climate change also threatens food security through indirect pathways. Disrupted transport routes due to landslides and floods frequently isolate communities, delaying food supplies and increasing prices. Given the region’s dependence on imports for staple foods, repeated disruption of road networks has a cascading effect on nutrition and household stability. In such settings, environmental shocks quickly translate into social stress, exacerbating inequality and deepening vulnerability among marginalized groups.

Infrastructure fragility further amplifies these risks. Gilgit-Baltistan’s strategic road corridors, including key sections of the Karakoram Highway, are vital for trade, mobility, and state presence. Climate-induced damage to these arteries not only imposes economic costs but also weakens emergency response and governance reach. Energy infrastructure, particularly small hydropower installations, is increasingly exposed to sediment-heavy floods and fluctuating river flows, threatening local electricity supply and economic activity. Each climate shock thus reverberates across multiple sectors, multiplying its overall impact.

The governance dimension is central to understanding climate change as a threat multiplier. While federal and regional authorities have taken steps to improve disaster risk management, capacity gaps remain significant. Monitoring of high-risk glacial lakes is uneven, local disaster management institutions are under-resourced, and adaptation planning is often reactive rather than anticipatory. In such conditions, climate stress interacts with institutional weakness, reducing the effectiveness of response mechanisms and prolonging recovery periods. This governance deficit transforms environmental hazards into persistent human security challenges.

Importantly, climate change in Gilgit-Baltistan also carries implications beyond the local level. The region is a critical upstream source for the Indus River system, meaning that cryospheric changes have downstream effects on water security, agriculture, and energy production across Pakistan. As upstream instability grows, so does the potential for inter-regional stress over water management and disaster response. In this sense, local human insecurity is linked to broader national and regional stability.

Addressing climate change as a human security issue requires moving beyond a narrow focus on disaster relief. Risk reduction must be integrated with long-term adaptation strategies that strengthen livelihoods, infrastructure resilience, and institutional capacity. Expanding early-warning systems, investing in climate-resilient infrastructure, and supporting community-based adaptation initiatives are essential steps. Equally important is embedding climate risk into development planning so that future investments do not inadvertently increase vulnerability.

A human security lens also highlights the importance of inclusive governance. Empowering local communities, incorporating indigenous knowledge into adaptation strategies, and ensuring equitable access to resources can reduce the social stresses that climate change exacerbates. International partnerships and climate finance mechanisms have a role to play, particularly in supporting technical monitoring, capacity building, and sustainable livelihoods in high-risk mountain regions.

In conclusion, climate change in Gilgit-Baltistan is not merely an environmental challenge; it is a force multiplier that intensifies existing human security risks across physical safety, livelihoods, food systems, infrastructure, and governance. The region’s experience illustrates how climatic stress can destabilize fragile systems and produce cascading effects that extend far beyond the immediate impact zone. Treating climate change as a core security concern rather than a peripheral environmental issue is essential for safeguarding human wellbeing in Gilgit-Baltistan and for strengthening resilience in the face of an increasingly uncertain climate future.