Underwater Drone Race in the Indo-Pacific: Impact on Regional Stability

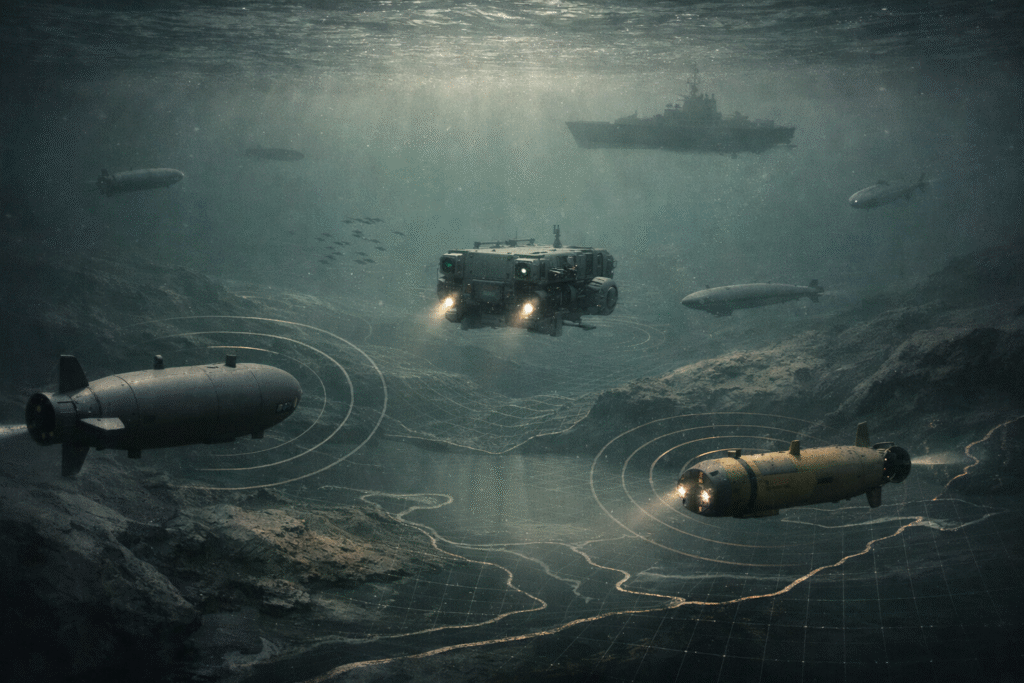

Several powers in the Indo-Pacific are striving to leap into underwater drone technology. As the world transitions towards autonomous systems, underwater drones are getting attention due to their affordability, reduced human cost, and operational benefits at sea. With China’s early steps into autonomous underwater vehicles, other regional actors, including Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, India, and Australia, are following suit, setting a new trend in the Indo-Pacific. Acquiring underwater drones helps in underwater detection, tracking, surveillance, deep-sea monitoring, underwater mapping, and neutralizing targets. States in the Indo-Pacific are increasingly realizing the potential of these capabilities; however, these systems carry the potential to transform the security landscape of the Indo-Pacific.

In January 2025, China conducted a test trial of an underwater drone dubbed “Feiyi,” a surveillance drone that can be launched from a submarine. It can transition between sea and air multiple times and return back to a submarine. After its initial launch, the drone’s blades open for flight and fold back for underwater navigation within five seconds. This helps reduce the resistance faced by the drone under the water. The design is inspired by ‘flying fish,’ which launch out of the water and glide long distances using wing-like fins. China is likely to build large swarms of these drones, offering the PLA Navy greater support in sea surveillance.

In addition, China is building extra‑extra‑large uncrewed underwater vehicles (XXLUUVs); two of its prototypes appeared in China’s 2025 parade in Beijing. Their size is equal to that of traditional submarines, capable of carrying torpedoes, sea mines, and smaller underwater vehicles. These capabilities are presumably designed to counter the US in the Pacific and Indian Ocean, or attack critical undersea cables as part of a Taiwan blockade.

As regional allies of the US, Japan and South Korea are equally focused on acquiring unmanned underwater systems to defend against China. In 2023, Japan’s ATLA (Acquisition, Technology & Logistics Agency) showcased for the first time the design of its extra-large uncrewed underwater vehicle (XLUUV) at the DSEI Japan defense show. Japan has officially named it a “long-endurance, multi-role UUV research prototype.” As the name “long endurance” implies, this UUV is designed to operate autonomously for an extended period, using a combination of Inertial Navigation System (INS) and Doppler Velocity Log (DVL) for positioning and velocity. This platform is currently under development and planned for multiple roles, including Intelligence Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR), Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW), mine hunting, and electronic warfare.

On the other hand, South Korea’s shipping firm Hanwha Group has teamed up with a US defense startup, Vatn Systems, to develop autonomous underwater drone swarms for the US Navy. These autonomous torpedo-shaped drones are designed for surveillance missions or as a strike weapon. The US Navy could potentially deploy these underwater drones in the South China Sea to protect Taiwan against Chinese invasion. In addition, the US Department of Defense is aiming to acquire an uncrewed underwater vehicle called Mantra Ray, developed by Northrop Grumman and last tested in May 2024. This underwater vehicle is payload-capable and designed for long-endurance and long-range operations in dynamic maritime environments. These developments show the US effort to counter China’s expanding naval presence in the Indo-Pacific.

Moreover, India’s increased spending on underwater military technologies demonstrates New Delhi’s ambitions for dominance in the Indian Ocean Region vis-à-vis China. Between 2024 and 2025, India conducted test trials of three unmanned underwater drones, including High Endurance Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (HEAUVs), Man-Portable Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (MP-AUVs), and Vamana Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs), while the fourth one, named Unmanned Launchable Underwater Aerial Vehicle (ULUAV), is under development. These newly developed underwater drones possess features similar to those of the Chinese underwater drones; however, with less range and fewer features.

Similarly, a QUAD member and critical US ally, Australia, aims to spend $1.1bn on a fleet of extra-large underwater “Ghost Shark” attack drones, which many believe would supplement the country’s plans to acquire sophisticated nuclear-powered submarines. Australia is focused on bolstering its long-range strike capabilities in an effort to balance China’s expanding military might in the Asia Pacific region. Ghost Shark is intended to engage in intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, and strike missions.

With all these developments, the implications are destabilizing for the region. First, the underequipped states, such as the Philippines and Taiwan, might be forced to enter the arms race and gear up production of underwater drones, especially as China consistently threatens both regional actors. Other powers, including Pakistan and North Korea, will have no option but to invest in underwater drones. As India prepares for Operation Sindoor, seeking new avenues for confrontation with Pakistan, the latter may want to protect its nuclear assets at sea. On the other hand, North Korea may be drawn into a potential conflict between the US and China; therefore, securing ballistic missile submarines will be a high priority for Pyongyang

Secondly, underwater drones might be employed for anti-submarine warfare in a potential conflict. This will simply disrupt the strategic stability because the region consists of five nuclear powers, including the US, China, North Korea, India, and Pakistan. A conventional conflict at sea could easily turn into a nuclear disaster. Additionally, due to the low cost of underwater drones and reduced human cost, regional states might employ these systems early in a conflict to attack the adversary’s submarines, ships, or vessels. This is another indication of how underwater drones can serve as a catalyst for nuclear war.

Thirdly, the increasing interest in the extra-large uncrewed underwater systems shows that the future conflicts at sea may not be confined to the peripheral waters of territorial zones. These long-range and high-endurance platforms might be employed for penetrating deep into the adversary’s coastal areas. As these systems evolve, states may want to increase their payload capacity, which means that these systems will be able to deliver massive damage. In addition, some states might develop countermeasures, such as underwater drone interceptors. However, all three challenges discussed are equally concerning. If an arms race continues at this pace, these underwater systems might serve as a recipe for nuclear disaster.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the policy or position of the Global Stratagem Insight (GSI).