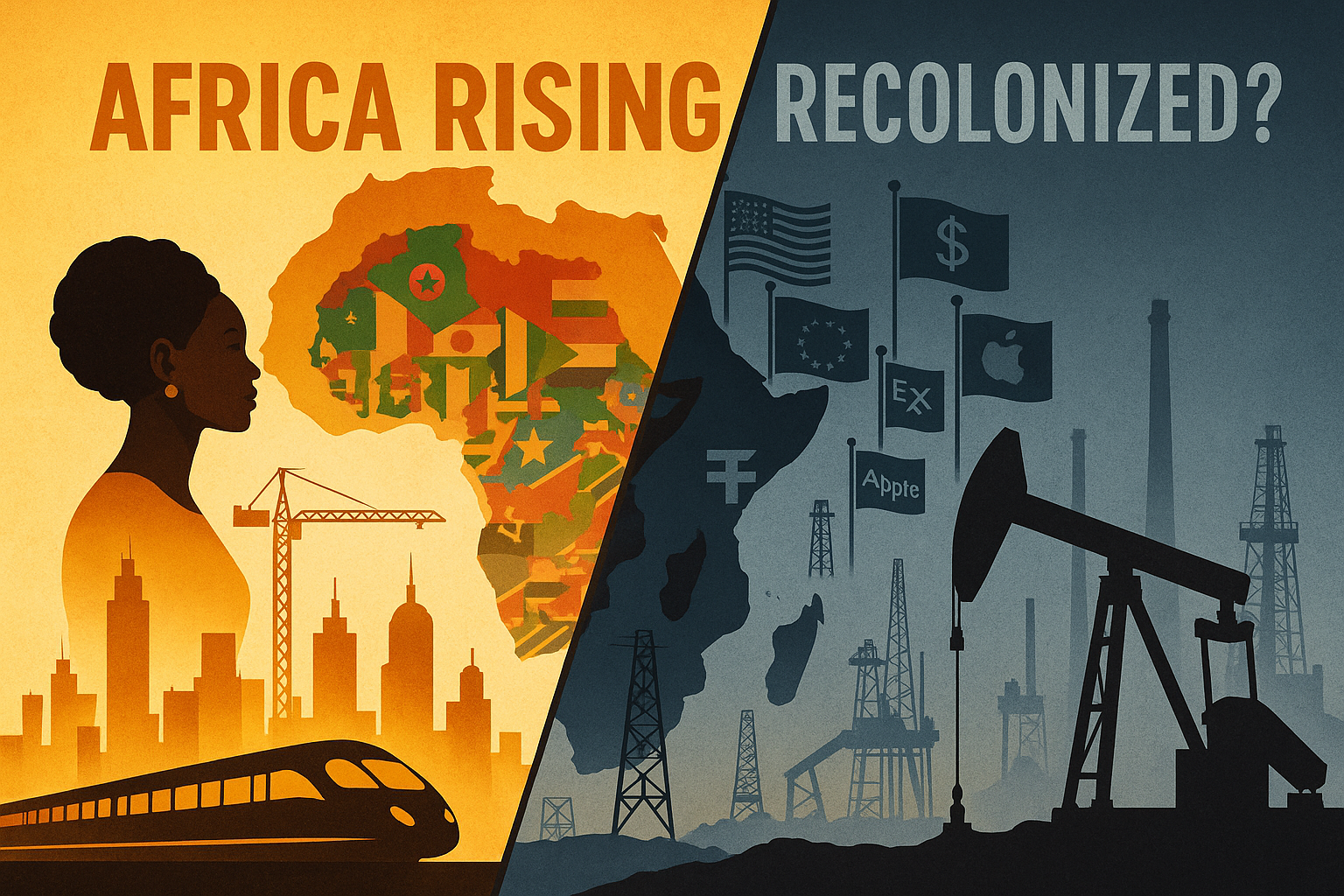

Africa Rising or Recolonized? Rethinking Foreign Investments in the Global South

A visual juxtaposition of Africa’s emerging development and the looming presence of foreign economic interests.

The sentiment towards Africa as ‘rising’ in the early 2010s received widespread coverage across international media and came as a result of optimism regarding the continent’s potential economic growth. Many African nations experienced an upsurge in GDP growth rates, surpassing the 5% mark between the years 2000 and 2014. This period marked a more optimistic view of the continent wherein it was considered as the next hotbed for economic opportunities due to increased urbanization, technological adoption, growth in the middle-class population, and other demographic factors.

Is another ‘Arab Spring’ simmering in the African Continent?

However, the narrative of hope and opportunity has dramatically shifted in the past 10 years. The supposed growth is instead a disguise for a complicated foundation of dependency and exploitation laced with geopolitical power plays. The Global South and largely Africa, it seems, is not rising on their own cognitions, but rather being forcibly integrated into a newly established global system of control disguised as foreign investment.

The staggering surge in foreign direct investment (FDI) into Africa is what drives the current transformation. As stated by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), foreign investment in Africa reached an all-time high of $97 billion in 2021, largely from investments in natural resources, infrastructure, and information technology. A good example is China, which has funded over $155 billion worth of African infrastructure projects using the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and other avenues since the year 2000. Not to be left behind, America, the EU, Turkey, Russia, and Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries have significantly been expanding their presence in Africa.

The investments acknowledge development in examination FDI-lead growth, put forward spending on infrastructural development along with emerging industries. Examples of these wide ranging investments includes rapid digital transformation of African countries. Although funding of this nature means supposed development, it is critical to evaluate the conditions and ramifications off such funding.

It is extractive in nature much worse off in most cases and empires of the colonial epoch’s duplicate resource extraction system. This is well illustrated by the example of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The DRC is host to more than 70% of the total global Cobalt reserves, constitutionally rated the “poor one” in Africa and has a contradictory name “sandwich state of assets,” multilayered represents the In what means is the Congolese mineral wealth of the population impoverished for the wealth of Palace bore the Congolese people meaning region people multi-miner voodoo capital power.

MNEs receive Cobalt from Congolese mines at cut rates most businesses without any qualm pay to discontinue surplus, people’s dislocation, child soldiers and environmental catastrophes.

This model of extraction is not only limited to minerals. Take agriculture for instance: the land grabbing phenomenon where land is leased, or up to millions of acres sold to foreign companies. Land Matrix reports that over 26 million acres of African land has been purchased by outside actors since 2000. These deals, which are claimed as modernizations of the agriculture sector, have resulted in the displacement of smallholder farmers as well as rising food insecurity because land is repurposed from local food production to export-driven monoculture farms.

Infrastructure, often considered a milepost of development, is in fact a two-edged sword. Construction of railways, highways and harbors by the Chinese has certainly upgraded certain logistical aspects of Africa, but most of these works are funded under heavily indebted contract deals which has sparked fears of debt-trap diplomacy. Take for example Zambia, which during the COVID-19 pandemic became the first African country to default on its debt.

This country was, among others, crippled by exorbitant spending on Chinese infrastructure works. In the year of 2022, the IMF reported that over 22 African countries were in or at high risk of debt distress. Many of these debts are hidden, incurred through bilateral deals without legislative and governmental scrutiny.

Perennial Capital issues in the Global South do not stem from foreign investment alone. In regard to the Global South, capital, technology, as well as civilizational contracts are foremost. Problems arise unwillingly when investments are designed at underwriting sovereignty, profiting, and dependency. Such investments do not catalyze developmental progress, they colonize. It’s particularly more worrisome in this context digitally. African digital structure is increasingly falling into the hands of foreign technology and telecom companies.

Huawei and ZTE from China are constructing 5G networks across the continent, while Google and Facebook are monopolizing vital data control. More often than not, data from African users is kept outside Africa, thus, raising critical issues about surveillance and Africa’s control over its own digital future.

The escalation of geopolitical competition among the greatest powers is molding Africa into a theater of influence not unlike the Cold War Era. The race for strategic resources, digital dominance, and maritime territories have incited a new wave of imperialism, masqueraded under development and partnership rhetoric. Special economic zones, military bases, and investment conferences serve as instruments of influence.

Russia hosted the Russia-African summit in St. Petersberg, China held the Forum on China Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), and the US arranged the Africa-US Leaders summit, all in 2022—each promising billions in trade and aid, while seeking alignment on UN votes, military alliances, and marketplace access.

Ashamedly not much of these geopolitical power struggles ignore the African agency. Developmental goals become achievable for countries like Rwanda and Ethiopia on account of their alignment with external powers, which strategically engage with them for deeper national interests. Operational since 2021, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) stands as a bold initiative aimed at transforming the continent from a raw materials exporter to a value-added goods manufacturer. If effectively implemented, AfCFTA has the potential to increase intra-African trade by more than 50% while creating an economic block with a total GDP exceeding $3.4 trillion.

Nonetheless, some challenges are structural. Weak governance, corruption, lack of transparency, and elite capture perpetuate predatory investment deals. Usually, foreign investors find willing partners among local elites who enjoy short-term monetary benefits, while the country’s long-term development suffers. Regulation is often inadequate, poorly defined, and enforcement is weak in practice, resulting in environmental and labor exploitation.

To reconsider foreign investment in the Global South—focusing on Africa—we need to shift from quantity to quality. Investment should be based on transparency and environmental impact, and they should involve community participation. African governments need to enhance their institutional capacity so they can better enforce regulations, demand mandatory technology transfer, and local content provisions. Civil society also needs to have the freedom to expose foreign interests and local powerholders.

In addition, cooperation among the Global South needs to be strengthened. South-South cooperation between Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia can counterbalance Northern-influenced economic structures. The African Union, CELAC, and ASEAN need to collaborate to offer better trade, knowledge exchange, and representation in global governance such as the WTO and IMF.

Africa is really doing better – in what ways and for who exactly? The continent’s future should not be framed by powers repeating patterns of domination under a new guise. Rather, Africa must rise on its own terms inspired by just partnerships, regional solidarity, and a vision that unequivocally puts human dignity, sovereignty, and sustainability at the core of development.

The option is neither simply aid versus investment, nor East versus West: it is recolonization versus self-determined growth. Whether Africa becomes a pawn of global powers or a post-colonial success story hinges on the policies its leaders make, the narratives its citizens demand, and the resolve to reshape the real meaning of development.